NOWRAMP

2002

Put

Your Face Where Your Feet Are!

Posted

by Dr. Larry Basch, Senior Scientist-Advisor, Pacific Islands

Coral Reef Program, National Park Service, & Associate

Professor, Graduate Program in Ecology, Evolution &

Conservation Biology, University of Hawai'i at Manoa.

October 22, 2002

At

the dawn of tank diving an eminent and wise marine biologist-professor,

Don Abbott, husband of Tutu Izzie, said to his students

- my mentors - who wanted to dive in pursuit of their research

that there are lifetimes of work and study still left to

do in the intertidal zone, that narrow and stressful yet

magical band of shore at times washed by the waves and at

others exposed to the air, and the heat and ultraviolet

rays of the sun. Fifty years and many research tank dives

later by his academic progeny and other successors, we've

learned lifetimes about the world beneath the waves. Nowadays

it's so relatively easy to put on a tank to dive and study

the biology, geology, or ecology of coral reefs and other

subtidal benthic ecosystems. During this era in the islands

of Hawai'i nei the intertidal has gotten pretty short shrift,

little attention has been paid to it, reflected today by

there being only two marine biology students out of hundreds

in Hawai'i whose research focuses on intertidal ecology.

At

the dawn of tank diving an eminent and wise marine biologist-professor,

Don Abbott, husband of Tutu Izzie, said to his students

- my mentors - who wanted to dive in pursuit of their research

that there are lifetimes of work and study still left to

do in the intertidal zone, that narrow and stressful yet

magical band of shore at times washed by the waves and at

others exposed to the air, and the heat and ultraviolet

rays of the sun. Fifty years and many research tank dives

later by his academic progeny and other successors, we've

learned lifetimes about the world beneath the waves. Nowadays

it's so relatively easy to put on a tank to dive and study

the biology, geology, or ecology of coral reefs and other

subtidal benthic ecosystems. During this era in the islands

of Hawai'i nei the intertidal has gotten pretty short shrift,

little attention has been paid to it, reflected today by

there being only two marine biology students out of hundreds

in Hawai'i whose research focuses on intertidal ecology.

Leading

up to this expedition I enjoyed meeting weekly with others

on the RAT - Research Advisory Team, planning the scientific

research and integrating it with cultural and educational

efforts for NOWRAMP 2002. I was originally asked to be an

REA - Coral Reef Rapid Ecological Assessment -- team member,

responsible for collecting data on marine invertebrates,

one of my intellectual passions. I was really looking forward

to diving and doing subtidal ecology in the NWHI - an opportunity

of a lifetime! But, for a bureaucratic reason I wasn't able

to strap a tank on my back and go to work as usual. Getting

past the questions and comments of many mystified colleagues

(like: that's BS; what do you mean you've done 1000's of

dives, you're a dive instructor; trained many, including

some aboard this expedition…) and my own initial disappointment

wasn't easy… until we reached our first island in the

Northwest chain - Nihoa! Shortly after we landed but before

the chants by our Kanaka Maoli shipmates were over,

I began to realize the incredible nature of the world between

the tides that we were now standing in and about to explore.

And it dawned on me that despite some earlier natural history

explorations that we, Jeremy Polloi- team limu-ologist and

the other half of the intertidal duo - were going to be

breaking new ground at every island, atoll and shallow reef

flat we traveled to!

Leading

up to this expedition I enjoyed meeting weekly with others

on the RAT - Research Advisory Team, planning the scientific

research and integrating it with cultural and educational

efforts for NOWRAMP 2002. I was originally asked to be an

REA - Coral Reef Rapid Ecological Assessment -- team member,

responsible for collecting data on marine invertebrates,

one of my intellectual passions. I was really looking forward

to diving and doing subtidal ecology in the NWHI - an opportunity

of a lifetime! But, for a bureaucratic reason I wasn't able

to strap a tank on my back and go to work as usual. Getting

past the questions and comments of many mystified colleagues

(like: that's BS; what do you mean you've done 1000's of

dives, you're a dive instructor; trained many, including

some aboard this expedition…) and my own initial disappointment

wasn't easy… until we reached our first island in the

Northwest chain - Nihoa! Shortly after we landed but before

the chants by our Kanaka Maoli shipmates were over,

I began to realize the incredible nature of the world between

the tides that we were now standing in and about to explore.

And it dawned on me that despite some earlier natural history

explorations that we, Jeremy Polloi- team limu-ologist and

the other half of the intertidal duo - were going to be

breaking new ground at every island, atoll and shallow reef

flat we traveled to!

Up

till now there's been little work done in the intertidal

of the NWHI other than collection of specimens and some

good "19th century" natural history. Now, there's

nothing bad whatsoever about natural history - it's key

to any meaningful rigorous ecological study. It's also fun!

Our goal was to add to that earlier knowledge. So we packed

our transect tapes and quadrats, sample bags and calipers

ready to get data - numbers - on sizes, abundance, distribution,

densities, and whatever else we could find about critters

and limu in the shallows. That's when reality came crashing

down, literally. The waves, many - way -overhead, smashing

onto the rocks were enough to make the most hard-stuck opihi

shudder. And much of the intertidal shore's rock faces were

shear vertical walls, dropping off into deep water. So,

it was pretty much impossible to lay meter tapes or put

down quadrats. Uh, time for plan B. Between huge sets we

looked or scrambled down to the mid- and low-intertidal

like 'A'ama crabs and picked up a critter here and

a clump of limu there. In most places this was all we could

do, spotting each other and the incoming waves as we moved

along the shore. On a few islands we were able to lay quadrats

down and get out our calipers to count and measure opihi.

And there are some tutu opihi out there, bigger than we've

seen living on the populated "lower" islands.

Recalling that many opihi pickers are killed every year

we were careful, wore life jackets, spotted and belayed

each other, trying to not bus-up our head. Now and then

a big set would wash over the opihi and us. One day, working

our way around to the windward side of Gardner

Pinnacle measuring opihi, a big sneaker wave came through.

All of a sudden I was surrounded by fast moving water --

lots of it -- and heard Jeremy calling out my name. I remember

putting one hand on top of my head while sliding down the

limu-covered rock 20 feet or so on my back and okole, totally

awash under the receding wave, then facing the rock, spinning

around and swimming hard away from shore before the next

big swell smashed into the rock. I turned around and gave

Jeremy the OK sign, then swam to safety, another near life

experience. Better than any water park attraction, if you

have a tough okole.

Up

till now there's been little work done in the intertidal

of the NWHI other than collection of specimens and some

good "19th century" natural history. Now, there's

nothing bad whatsoever about natural history - it's key

to any meaningful rigorous ecological study. It's also fun!

Our goal was to add to that earlier knowledge. So we packed

our transect tapes and quadrats, sample bags and calipers

ready to get data - numbers - on sizes, abundance, distribution,

densities, and whatever else we could find about critters

and limu in the shallows. That's when reality came crashing

down, literally. The waves, many - way -overhead, smashing

onto the rocks were enough to make the most hard-stuck opihi

shudder. And much of the intertidal shore's rock faces were

shear vertical walls, dropping off into deep water. So,

it was pretty much impossible to lay meter tapes or put

down quadrats. Uh, time for plan B. Between huge sets we

looked or scrambled down to the mid- and low-intertidal

like 'A'ama crabs and picked up a critter here and

a clump of limu there. In most places this was all we could

do, spotting each other and the incoming waves as we moved

along the shore. On a few islands we were able to lay quadrats

down and get out our calipers to count and measure opihi.

And there are some tutu opihi out there, bigger than we've

seen living on the populated "lower" islands.

Recalling that many opihi pickers are killed every year

we were careful, wore life jackets, spotted and belayed

each other, trying to not bus-up our head. Now and then

a big set would wash over the opihi and us. One day, working

our way around to the windward side of Gardner

Pinnacle measuring opihi, a big sneaker wave came through.

All of a sudden I was surrounded by fast moving water --

lots of it -- and heard Jeremy calling out my name. I remember

putting one hand on top of my head while sliding down the

limu-covered rock 20 feet or so on my back and okole, totally

awash under the receding wave, then facing the rock, spinning

around and swimming hard away from shore before the next

big swell smashed into the rock. I turned around and gave

Jeremy the OK sign, then swam to safety, another near life

experience. Better than any water park attraction, if you

have a tough okole.

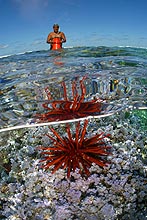

Jeremy

and I have now worked every island, atoll or pinnacle with

basalt or limestone (old coral reef) rock habitat in the

Kupuna islands. Working the benches, terraces, walls, and

beaches, and free-diving to cover the lower reaches of the

intertidal and the shallow waters just offshore, we've enjoyed

the freedom and ability to approach these habitats on their

terms, whether dodging the waves or swimming below the surface

without the noise of bubbles from a scuba rig, and being

tossed around in the surge with the fish. We've asked a

lot of questions but we've really just scratched the surface.

There are several student theses-worth of work to do in

the future here in the Kupuna's. We've started putting our

heads together and some interesting patterns are coming

out, especially about biogeography or the big-picture on

distribution of intertidal organisms -- which islands and

environments they live at across the NW stretches of the

archipelago, and why. We've learned that there are a lot

of subtle things out there between the tides, ones that

are so easy to miss. Indeed, Tutu kane Don is still

right: there are worlds in the intertidal as yet undiscovered,

… if you put your face where your feet are.

Jeremy

and I have now worked every island, atoll or pinnacle with

basalt or limestone (old coral reef) rock habitat in the

Kupuna islands. Working the benches, terraces, walls, and

beaches, and free-diving to cover the lower reaches of the

intertidal and the shallow waters just offshore, we've enjoyed

the freedom and ability to approach these habitats on their

terms, whether dodging the waves or swimming below the surface

without the noise of bubbles from a scuba rig, and being

tossed around in the surge with the fish. We've asked a

lot of questions but we've really just scratched the surface.

There are several student theses-worth of work to do in

the future here in the Kupuna's. We've started putting our

heads together and some interesting patterns are coming

out, especially about biogeography or the big-picture on

distribution of intertidal organisms -- which islands and

environments they live at across the NW stretches of the

archipelago, and why. We've learned that there are a lot

of subtle things out there between the tides, ones that

are so easy to miss. Indeed, Tutu kane Don is still

right: there are worlds in the intertidal as yet undiscovered,

… if you put your face where your feet are.

<<Journals

Home