|

You

are here: /main/research

expeditions/June-July

2006/ Day 9

Counting Fish in the New Marine National Monument

By Claire Johnson, NOAA National Marine Sanctuary Program

With approximately 6 days of transit to reach Kure Atoll, there

was ample time to prepare for the unique experience we

are about to embark on. One of the objectives of the education

team

is to collect data for the Reef Environmental Education Foundation

(REEF) on fish species abundance and diversity. To date,

there have only been 21 surveys conducted in the Northwestern

Hawaiian Islands, as compared to thousands of surveys

conducted by volunteer snorkelers and divers in the main

Hawaiian Islands and other locations around the world.

The data we collect

on this trip will be added to the REEF online

database, which can aid

resource managers in making informed ecosystem-based management

decisions.

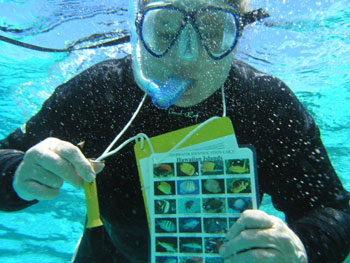

Teacher Dena Deck gets familiar with the species found in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Photo: Hans Van Tilburg/NOAA

The transit allows our team to brush up on our fish species identification, or for the two teachers

from Florida and California, to begin the process of positively identifying the fish we will most

commonly see in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument. Through slideshows,

field guides, video footage and conversations, each day the educators become more proficient in

fish species identification. We are learning special things about each species; including life

histories and if each species is endemic, indigenous or alien. We will be contrasting endemism

frequency in fish species between the Main Hawaiian Islands and the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

From the data collected initially by the 21 surveys previously conducted in the Northwestern

Hawaiian Islands, the most commonly seen fish in order were: saddle wrasse (Thalassoma

duperrey),

milletseed butterflyfish (Chaetodon miliaris) Hawaiian cleaner wrasse (Labroides

phthirophagus),

manybar goatfish (Parupeneus multifasciatus) and spectacled parrotfish (Scarus

perspicillatus).

Four of these commonly seen species are also endemic to the Hawaiian Archipelago, excluding the

manybar goatfish. Having personally experienced diving many times in the Channel Islands National

Marine Sanctuary off the coast of California, the preliminary data (which is limited at this time)

suggests that these species are similar to the species frequency of fish such as the blacksmith

(Chromis punctipinnis) and senorita (Oxyjulis californica). You will almost always see blacksmith

and senorita on any dive in a kelp forest around the Channel Islands as you would find an endemic

saddle wrasse on nearly every dive in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Naturalist Ellyn Tong dives deep during a reconnaissance dive at a new location on the outside of Kure’s lagoon. Photo: Claire Johnson/NOAA

All gear needs to soaked in a water/bleach solution before entering these near-pristine waters.

This will help alleviate the accidental introduction of alien algae or other nuisances that may

upset the balance of the fragile coral reef ecosystem in this remote location. These precautions

aren’t taken everywhere in the country, but for an isolated location as unique as the Northwestern

Hawaiian Islands, this strategy is imperative. All boats, skiffs and ships need to have their hulls

cleaned and ballasts emptied before they embark on a voyage to the farthest reaches of the Hawaiian

Archipelago. Resource managers have learned from other’s experiences, such as the invasive zebra

mussels in the Great Lakes that likely entered the lakes through ballast waters, to have strict

protocols.

During a few days of diving in the lagoon of Kure Atoll, we have already seen a great diversity

of species and generally I would say that the biomass here in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

surpasses the biomass at the popular dive locations around the Channel Islands that I am familiar

with. This is likely due to a large population living in close proximity to the Channel Islands

and the numerous fisheries that exist there. Whereas, there are no recent nearshore fisheries

in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and limited offshore fisheries to have the same impact on

biomass of reef fishes. There are many divers collecting REEF fish census data in the Channel

Islands, so the new no-take marine reserves in the Channel Islands can be a nice comparison to

see how the biomass of these marine protected areas increases over time and spill over into

the areas that can be fished. During one of our snorkels today, we also found what we

affectionately call a fish nursery, since a large percentage of what we saw was a juvenile

or young of the year. The canopy of a healthy kelp forest off the Channel Islands offer

similar protection as the nooks and crannies found in a protected and sheltered coral reef ecosystem.

A giant trevally known as ulua in Hawai`i, is one of the apex predator fish commonly found in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Photo: Claire Johnson/NOAA

There is also a nice balance of apex predators in the Northwestern Hawaiian

Islands that isn’t really

found in any other marine ecosystem in the world. These are all reasons

of why this area is so unique and should be conserved for future generations.

Our country is on its way to this type of protection

with the President’s proclamation making the world’s largest marine protected

area – the Northwestern

Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument. I can only hope that this unbelievable

place is kept intact for my child and my children’s children to learn about

and maybe even get a chance to experience first-hand.

|